What Translation Studies Can Teach Us About Living with AI in Education

Why Mastering Human Expertise First Makes All the Difference

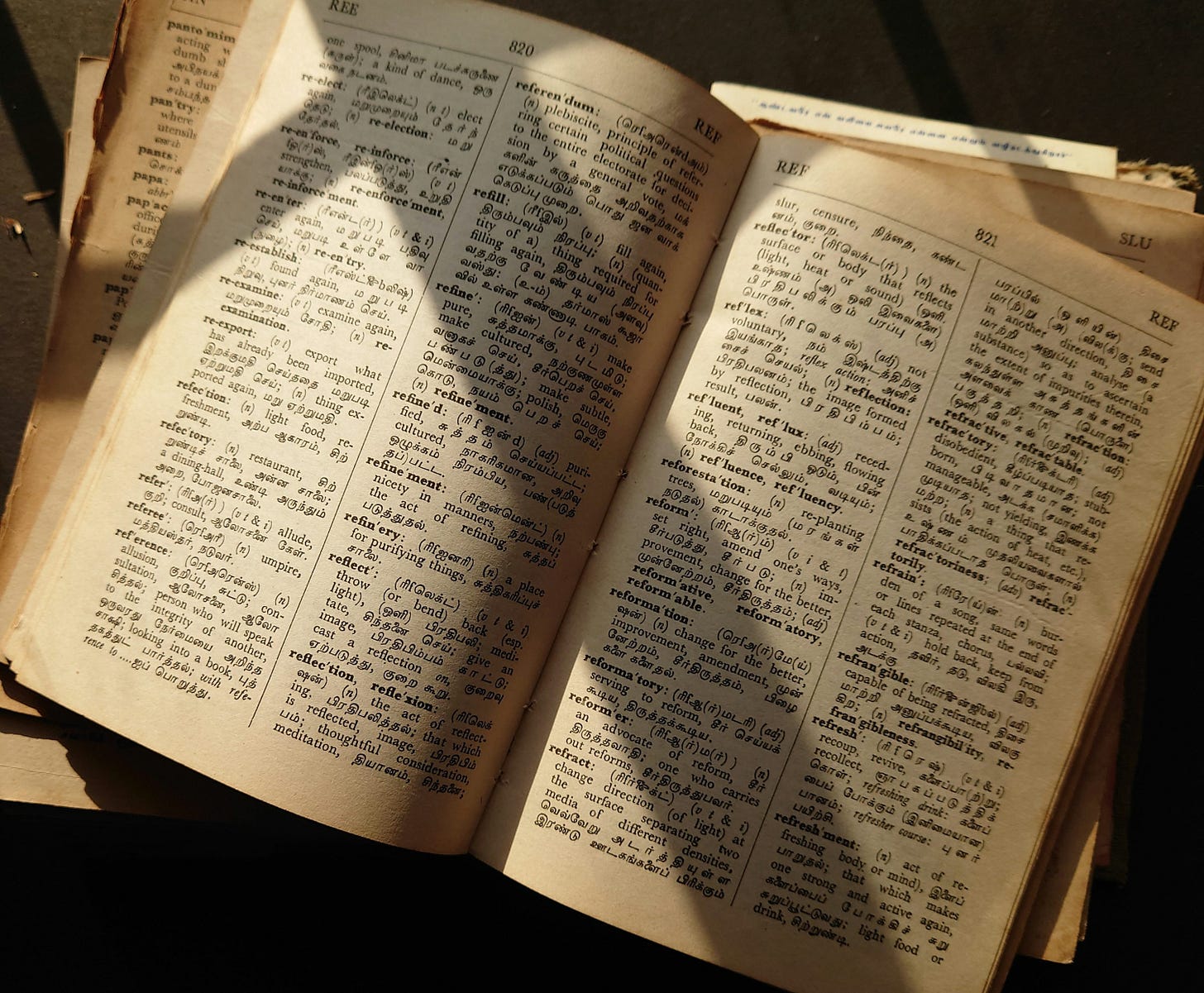

While educators across disciplines scramble to figure out how to integrate AI tools into their curricula, one field has been quietly navigating this challenge for nearly two decades. Translation studies offers a compelling model for how education can adapt to AI—not by fighting it or rushing to embrace it, but by fundamentally strengthening human expertise first.

The Patient Approach: Fourteen Years of Watching and Learning

When Google Translate launched in 2006, translation programs didn't panic. They didn't immediately overhaul their curricula or ban the technology. In a way, they waited and watched.

At the University of Salamanca, my alma mater and one of Spain's top translation schools, the core curriculum remained essentially unchanged from 2010 until this year—2024. This wasn't stagnation; it was strategic patience. While machine translation evolved from clunky word substitution to sophisticated neural networks, translation educators were quietly observing what skills would remain essential and what new competencies would emerge.

The result? A measured integration that prioritizes human expertise while embracing technological tools.

Foundations First

Here's what surprised me most when I started studying translation in 2007: we didn't jump straight into translation courses. Instead, our first year was dominated by intensive language study—not just our second languages, but most importantly, our native Spanish.

Our professors would proudly tell us that the Spanish courses we were taking were more rigorous than those required for journalism degrees. This seemed backwards at first. Why spend so much time perfecting skills in a language we already spoke fluently?

The answer became clear as machine translation improved. Translators work primarily into their native language, and exceptional writing skills in that language became the foundation that made everything else possible. You can't evaluate whether an AI translation captures the right tone, maintains stylistic consistency, or preserves subtle meaning unless you have mastery over language yourself.

As AI tools became more sophisticated, something interesting happened in translation education: the emphasis on human judgment intensified rather than diminished. The question shifted from "How do we translate this?" to "How do we know if this translation is good?"

This created a new pedagogical focus on developing what we might call "quality assessment literacy"—the ability to rapidly identify when AI output misses the mark and understand why. Students learned to spot not just obvious errors, but subtle problems: cultural insensitivity, inappropriate register, or loss of authorial voice.

This skill proved transferable far beyond translation. It's essentially the same competency needed to evaluate AI-generated essays, code, or research summaries.

Strategic Integration, Not Wholesale Adoption

When Salamanca finally updated its curriculum in 2025, the changes were telling. Computer science applied to translation moved from a junior elective to a freshman requirement. New technology courses appeared throughout the program. But the core remained intact: rigorous language training, translation and interpreting strategies, and specialized domain knowledge.

The message was clear: AI proficiency is essential, but it's built on top of fundamental human expertise, not instead of it.

The Reality Check: We Can't All Go Slow

The translation studies model offers valuable lessons, but we need to be honest about the constraints facing other educators today. Unlike translation programs, which had the luxury of observing machine translation's gradual evolution from 2006 onwards, most fields have been thrust into the AI revolution overnight.

Today's educators are dealing with an immediate crisis: they're grading essays they suspect were written by AI, with no reliable way to prove it. They're being pressured to overhaul their teaching methods and assignments without clear guidance on how to do it effectively. The frustration is real and urgent.

Translation studies can't solve this timing problem, but it can offer a framework: prioritize developing students' ability to evaluate and improve AI output rather than simply detect and prevent its use. Focus on assignments that require the kind of critical judgment that comes from deep subject mastery.

The Transferable Skills Advantage

I'd be naive to ignore that fewer translators are needed in traditional roles. Friends working for pharmaceutical companies have seen entire translation departments eliminated. The field is undergoing significant disruption.

But here's what's remarkable about translation studies: the skills prove incredibly transferable. My classmates from 2007 are now working across industries—marketing, banking, teaching, sales, international affairs, publishing. The program may have been called "Translation and Interpreting," but what we really learned were meta-skills that apply far beyond language work.

We learned how to learn rapidly when encountering specialized content. Translating a technical document requires you to deeply understand what it's saying, not just convert words between languages. We developed exceptional communication skills, learned to structure and organize complex information, and became experts at finding and evaluating sources.

Most importantly, we learned to work with imperfect tools—dictionaries, glossaries, early machine translation—and developed the judgment to know when to trust them and when to intervene. This is exactly the skill set other fields need now.

Lessons for Education Broadly

Translation studies suggests three key principles for educational AI integration:

Strengthen foundational skills first. Before students can effectively use AI tools, they need mastery of the underlying discipline. You can't prompt-engineer your way around not understanding the subject matter.

Develop critical evaluation capabilities. The most valuable skill in an AI-assisted world isn't generating content—it's recognizing quality, identifying errors, and understanding when human intervention is needed.

Integrate gradually and strategically. Rather than reactive adoption, translation programs demonstrate the value of patient observation and deliberate integration based on evidence rather than hype.

The Advantage of Going Second

Translation studies had a crucial advantage: time. While machine translation evolved gradually from 2006 to the ChatGPT moment, educators in this field could experiment, observe, and adapt their approaches based on real evidence rather than speculation.

Other disciplines, hit seemingly overnight by generative AI, can learn from this measured approach. The panic to immediately overhaul curricula might be less productive than the translator's strategy: strengthen human expertise, then layer in AI literacy as a powerful but supplementary tool.

The question isn't whether AI will transform education—it already has. The question is whether we'll learn from fields that have successfully navigated this transformation, or whether we'll repeat their early mistakes while missing their hard-won insights. Without intentional integration, students will use AI in ways that undermine their skill development, never learning the foundational competencies they need to use these tools effectively.

Translation studies shows us that the future isn't human versus AI—it's humans with AI, guided by deep expertise and critical judgment that only comes from mastering the fundamentals first.