A few months ago, I was at a book launch in a delightful book store in NYC (Rizzoli, if you're into arts and fashion, you should check it out). The writer's wife, who happens to be Roxane Gay, another famous writer, was also there. Roxane mentioned a play they had recently seen, a clear example of how it's impossible to fully be yourself in a language different from your mother tongue. The guy sitting next to me immediately looked at me. I had just told him I have a Ph.D. in Second Language Acquisition. You can imagine where my eyebrows went. I shook my head and mumbled, "I don't think I agree with that". I obviously bought tickets to go see it as soon as I got home.

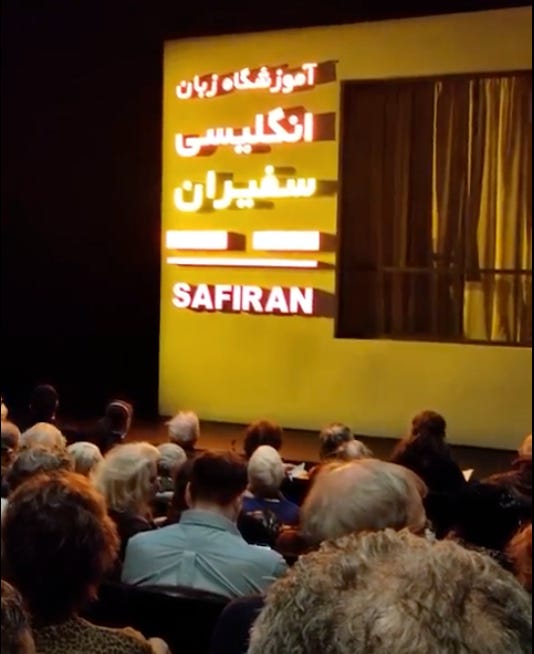

The play was called English by Sanaz Toossi. As I walked into the theater, I was surprised by the average age of the audience (I would say 70), 95% white. The play tells the story of a group of Iranian students taking English classes to pass the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). Any international student in the US has suffered this test. I've actually taken it three times and could definitely relate to the students in the play. Also, I have a master's in teaching Spanish as a second language, so I related to the instructor as well. Which means I could relate to all five actors in the play. Everyone, you might think. But no. I couldn’t relate to the audience. Let me explain why.

Marja, the Iranian teacher, insists on speaking only English in the class. The students are not advanced yet, and struggle to convey complex ideas. Importantly, they have an accent, an Iranian accent. The audience found this Iranian accent hilarious. I, on the contrary, couldn’t stop crying. I wondered whether the audience was aware of the impact of their laugh, whether anyone had laughed at them because of their accent. I thought of my students, who have all sorts of accents. And I felt protective. They work relentlessly on improving, and a laugh on your accent can hurt deeply. I've heard so many stories of people who quit studying a language because someone laughed at their accent once (check the comments on my TikTok for hundreds of examples). “I still have his laugh stuck in my head” a colleague once told me while explaining why she didn’t think she was good at Spanish.

In the booklet, the playwright grappled with the accents. She explicitly gave permission to laugh at the students' accents, but for the right reasons. We've all heard an adult language learner sounding like a 3-year-old (if you've ever studied another language, you've been the 3-year-old). Toossi hoped first-generation Middle Eastern kids would watch the play and laugh because they'll hear their parents’ accents, a very different laugh indeed. Our accent tells a story about where we are from, both geographically and socioeconomically, it’s inextricably linked to our identity. It's not surprising that someone laughing at our accent makes us feel rejected.

I often think about the parallelisms between ethnicity and accent. You can't hide them. And both are taboo. I've been a foreigner almost my entire adult life, and I'm very comfortable in that skin. One of the best parts of being a foreigner in the US is that there are many of us. I'm naturally attracted to them. As soon as I notice a non-American accent, I can't help myself, I have to ask. I'm legitimately curious to know where they come from, they are like me, but different. However, I've noticed many people don't dare to ask, as if being a foreigner was bad. I see how bad they want to ask me where I am from, but they refrain until I ask first. My foreign condition (even alien, as the US government likes to call us) makes it easier for me to ask. This is no different from the discomfort white people feel talking about race. We avoid saying "that person is black" because we've been taught being black is bad.

Sometimes, people seemed bothered by my accent. I remember a doctor who ask me to repeat my answers multiple times, I wonder whether he pretended not to understand me; or a guy I met in a bar who turned around and told his friends "Oh my god, she has such a strong accent". I could tell that they were not interested in talking to me, even by the way they moved, there was something in their body posture signaling "you're making me work too hard, please disappear". I used to feel bad about it, like my English was deficient. But I've changed my mind. I know my accent is perfectly understandable (I've won a “best presenter award” at an international conference!). But I also know that the sound waves coming out of my mouth are different from the ones native speakers of English make. So what? Why are we so obsessed with perfectly aligning our sound waves with those native speakers make? I've come to realize that what's deficient is their listening, not my speaking. Saying that we all must sound native is like saying that we all must be blond.

Now that I live in NY, accents are everywhere. They are normal, and most people don't even blink about them. I walk around my block in Queens and I hear more accents and languages than I can count. As I enter my building, the super greats me with a strong Serbian accent, I hear Portuguese Fado coming out from one of the apartments as I walk upstairs, and when I close the door of my apartment, I watch the Spanish news on my iPad, while hearing Tamil through the wall from my next-door neighbors' TV. Living in such a diverse community makes you a better listener. I can’t help but think how lucky I am.

P.D.: Roxane, if you ever read this, yes, you can be fully yourself in your second language. Millions of immigrants have learned to do it. There might be ideas we would like to tell you in our first language, but we find a way. And when we go to our home countries, we wish we could use English to express other ideas 😉