Photo by Jerry Wang on Unsplash

When I was a kid, I was good at studying. It came easy to me, it was easy to remember things, to see the logic behind them. There were only two classes I knew I wasn’t good at: arts and physical education. But people didn’t seem to think they were important, so I didn’t feel the need to try to get better. Do you see a problem there? I hope you do.

This semester, I’m in a program to support publication writing among junior faculty in CUNY. We get a course release (for the non-academics, I teach one course less than what my contract says) and we are paired with three other junior faculty and a mentor. I was told this was the best program at CUNY and, after two meetings, I couldn’t agree more (actually, CUNY, if you’re reading, give us more stuff like this). The basic premise is two people submit a draft (in my case, an article) and the rest gives you feedback. I volunteer to go first and I noticed my colleague submitted her work a couple of hours before me. I didn’t dare to open hers before submitting mine because I was scared hers would be fabulous, mine 💩 , and I wouldn’t have time to fix it. I shared my experience with them, and our mentor —Mark McBeth— took advantage of the moment to explain the goodness of shitty first drafts.

Shitty drafts are the bridge to getting real feedback, to improving. This program lets us see the work behind every piece of writing. I want to emphasize the word EVERY. Mark continued to say: “perfect drafts are disrespectful”. They deceive the reader by leading them to think it came out that good on the first try, straight out their heads. Perfect drafts hide the real effort that took to get there. And you know when you learn a new word and you start seeing that word everywhere? I’m having the same experience with ideas.

I just read Think Again, by Adam Grant. The book is about the importance of reconsidering our beliefs, about how we change our t-shirts to match the latest fashion trend, but we let our beliefs be guided by what our uncle said during lunchtime when we were 5. Two examples in the book brought me back to my dear shitty first drafts. One was about a professor who chose to teach a different class every semester. As a junior faculty myself, my first thought was: this man is nuts, doesn’t he need to publish? Details aside, for him, teaching was a way of learning. Rather than presenting a perfect class to students, he presented an imperfect class that gave students space to improve. Much like my shitty first draft that my colleagues were eager to give me feedback on. It made me think about how much space I give my students to improve.

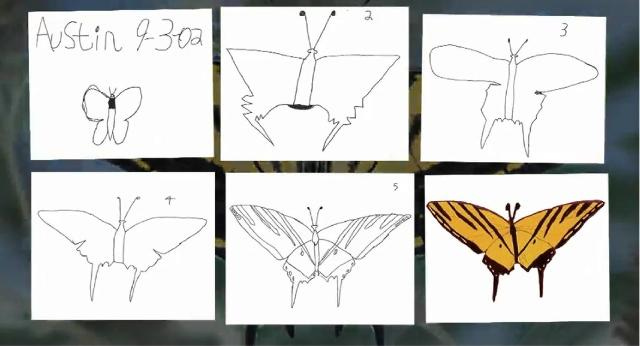

The second example was a story about a 6-year-old who went from drawing a shitty butterfly to a beautiful one with feedback from his classmates.

You can watch the process with the kids here. What I loved about the story is that kids that are taught this way start asking for another opportunity to get better. They learn about the process and instinctively apply the same technique to other areas. I kind of want to go to school with Austin. It also made me think about the tremendous importance of our environment. If you see read a manuscript equivalent to butterfly #1, what’s your first reaction? What allowed Austin to get to his final butterfly was a positive environment that provided constructive feedback. And that is precisely what I’m getting out of my colleagues and mentor in the writing program.

I wish someone had taught me about the process in my physical education class (rather than giving me an A because I had As in the rest of the classes). You will inevitably reach a point where things are not easy anymore. Think about Austin then.